Tracing History: Village, Monastery, Campus

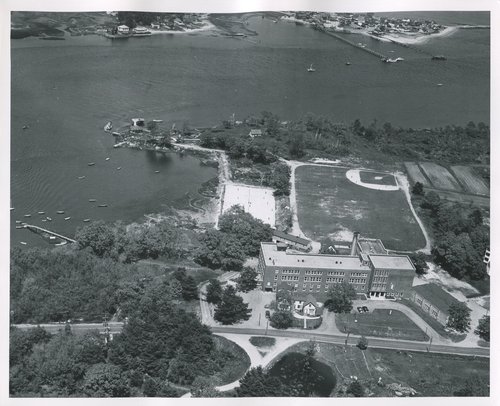

Aerial view of Saint Francis College, 1955.

Land acknowledgment: The Biddeford campus of the University of New England is situated on the unceded, traditional homelands of the Wabanaki people. Traces of indigenous peoples’ lives and activities exist in the soil under our feet and in the waters that surround the UNE campus. We acknowledge and honor the stewardship of this land we now call Maine by the Abenaki, Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot people, along with all of the tribal communities that inhabited this land for over 12,000 years. We acknowledge the current and future work necessary on the part of non-Native people towards cultural equity and reparation.

If you are interested in learning about current efforts for Wabanaki sovereignty, librarians can help to connect you with resources.

Freddy Beach, University of New England. Photograph by Ben Fitzgerald, 2023.

Standing where the land meets the water at Freddy Beach, the October air is crisp and the wind creates gentle waves in this otherwise calm cove. The deciduous trees are beginning to turn orange, yellow and red, signaling the start of the colder season of the year. Students arrive for a class that examines the archaeological traces of indigenous settlements at the shore. Looking out at the ocean, it is possible to imagine standing here in another era, the tide lapping at the shore.

Early history of the land

Students from UNE and the University of New Brunswick excavating in 2019. Image courtesy of Arthur Anderson.

In the late Pleistocene, what is now Maine was covered with ice about a mile thick. As the ice receded, rivers and shorelines changed as the sea level rose with the melting of ice. The first known inhabitants of this region can be traced to between 12,000 and 13,000 years ago. The southern part of the coast was forested with spruce, fir, birch and poplar. At the end of the ice age, vegetation changed to include more nut-bearing trees and a greater variety of species. The site where the UNE campus now stands has evidence of human habitation dating back about 3,000 years.

European exploration of the coast

A broken projectile point from the Woodland period, made out of rhyolite, a volcanic rock, from Vinalhaven. Image courtesy of Arthur Anderson.

When Champlain arrived at the mouth of the Saco [Chouacoët] he was greeted by a group of Almouchiquois people who later invited him into their village. From there he made detailed observations of his visit [see illustration of his 1605 chart]. Some structures were near the coast while others were more inland, suggesting organized settlements. Champlain illustrated agricultural plots, which were notable in this region compared to areas he had visited farther north along the coast. The main villages were inland, roughly where the UNE campus stands, and along the Saco River.

Drawing of the Saco Bay area from Les Voyages Samuel de Champlain (Image courtesy of the Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine.)

Champlain notes some of the people’s agricultural practices in detail, which we would now identify as a “Three Sisters” planting of corn, beans and squash together. Indigenous agricultural technologies are now recognized as deeply sophisticated systems. We can see Champlain’s acknowledgement of that fact in his description:

“We saw their Indian corn, which they raise in gardens. Planting three or four kernels in one place, they then heap up about it a quantity of earth with shells of the signoc before mentioned. Then three feet distant they plant as much more, and thus in succession. With this corn, they put in each hill three or four Brazilian beans, which are of different colors. When they grow up, they interlace with the corn, which reaches to the height of from five to six feet; and they keep the ground very free from weeds. We saw there many squashes, pumpkins, and tobacco, which they likewise cultivate.” (Champlain 62)

Archaeological evidence of indigenous inhabitants

There have been numerous archaeological digs throughout the last hundred years that examined places along the shoreline and further inland on campus. During the early construction of the Marine Science Center on the University of New England campus, shell heaps were discovered on the land, suggesting established cooking areas. In the past decade, Dr. Arthur Anderson, who teaches archaeology at UNE, has led teams to examine the traces of indigenous life along the coast. During recent digs, shell heaps and burnt scuds from sturgeon were found at Freddy Beach. There is also an indication of a hearth. Dr. Anderson surmises that the beach was used as a working zone where tools were made and repaired, animals were cleaned after hunting and fishing; fat may have been rendered, and canoes docked.

Early European settlers

While this area's indigenous inhabitants left only traces of their activities, early settlers constructed cemeteries that still exist on this site. The Jordan family plot sits across from the Campus Center (right off the sidewalk by the parking lot), and the early town burial ground is under the trees near the Petts Center.

The Jordan Farm was owned by Captain Samuel Jordan from 1684-1742, and kept in the family until 1931 when Estelle Tatterson and her sister sold the property to Reverend Arthur M. Decary, where the Stella Maris Children’s Home and convent was established by les Soeurs de la Présentation de Marie. The home operated as an orphanage and a boarding school until the late 1930s. Adjacent to the Jordan Farm was the Flood's Shore Dinners, owned by Abbie L. Flood. This was a popular eatery, visited by people from all over the continent. In 1934, Flood sold the house to the Franciscans, who converted the building to their friary. For years after the sale, potential diners stopped at the friary to ask if they could buy a shore dinner.

In 1933, Father Decary was the priest for St. Andre’s church in Biddeford. His assistant, Father Venon served as the chaplain for the Stella Maris convent. In 1934, Father Frederic came to Biddeford and established the Franciscan school program. When the Franciscans purchased the Flood House, they were able to move their quarters to that home and use Stella Maris as a school. The St. Francis High School was founded in 1939, beginning with just 12 students. (“St. Francis School and College at Biddeford Born of Priest’s Lack of Help in Huge Parish” by Elmer Ingalls. Bangor Daily News. August 12, 1952. St. Francis College Scrapbook, 1933-1952, St. Francis College History Collection)

St. Francis High School and College

St. Francis College was established in 1939 on the mouth of the Saco River in Biddeford, Maine, a high school and junior college for young Franco-American men. It was the first French school in New England. The first class of nine graduated in June 1943.

The College redefined its mission around programs in the biological sciences, human services, and business administration. Partnership with the New England Foundation for Osteopathic Medicine led to the founding of the New England College of Osteopathic Medicine on the campus in 1978, and the creation of the University of New England as one institution.